A revival of British

Sleeper Trains is coming to enjoy us.

by Alexander Naughton, editing by Earl of Cruise

by Alexander Naughton, editing by Earl of Cruise

Sleeper Trains epitomise

the romance of travel and have a magic touch and cosmopolitan spirit to them as

you go to sleep in one location and wake up refreshed in another. They are

convenient, cost effective and environmentally friendly ways to travel. These

lifeline trains allow people to make connections – for business, leisure and

family – in a way that no other mode of transport can. In recent years, sleeper

trains in Britain have experienced a great revival in their fortunes.

Photo: Travel poster of LMS Night Scot sleeper

train from London to Scotland

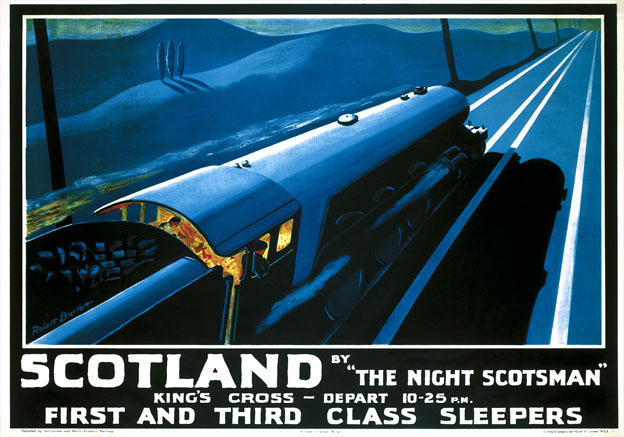

Photo: Travel poster of LNER Night Scotsman sleeper

train from London to Scotland

However this is in direct

contrast to what is happening with sleeper trains in Continental Europe where

they seem to be in decline due to the advent of low cost air travel,

development of high speed rail, lack of investment and promotion.

This article

looks at the background to sleeper trains in Britain and the factors that are

contributing to their revival in recent years including investment and

promotion.

BACKGROUND:

Sleeper trains have

operated in Britain since Victorian times and offered comfortable overnight

accommodation on long distance and some medium distance journeys, allowing

passengers to leave their home station in the early and late evening and arrive

at the destination at a civilised time the following morning. Often they

conveyed restaurant cars, so that dinner could be enjoyed before retiring and,

on longer journeys, breakfast in the morning. The earliest sleeper carriages

were introduced in Britain in 1873 by the North British Railway on the

Anglo-Scottish route between Glasgow and London Kings Cross. This and other

pioneering sleeping carriages in the UK, including the early Pullman sleeping

cars imported from the USA, had communal sleeping, with longitudinal berths

convertible from seats.

Photo: GWR First Class Sleeping Car No 9038 built

in 1897 at Swindon Works and used until 1931 on the London Paddington

to Fishguard Harbour sleeper trains. At Fishguard Harbour there were

connections with the ferry services to Ireland. This carriage now preserved at

West Somerset Railway.

The first sleeping car

train on the Great Western Railway was introduced at the end of 1877 from

London Paddington to Plymouth. This had 7 ft (2,134 mm) broad gauge carriages

with two dormitories, one with seven gentlemen’s berths and the other with four

ladies’ berths. These were replaced in 1881 by new carriages with six

individual compartments. An additional service was soon added from London to

Penzance which eventually became known as the forerunner of today’s Night

Riviera.

The Great

Western Railway introduced the familiar sleeping car layout with an internal

side corridor and compartments containing berths. This became the British

conventional sleeping car, introduced by a variety of railways. The main

sleeper trains services in Britain gradually became focussed on the following:

- London to Scotland

(Anglo-Scottish services)

- London and the West

Country (Devon and Cornwall)

- London and northern

cities.

- London to

Paris and Brussels (via train ferry) The Night Ferry

Flagship sleeper

services included the following titled trains:

- The Night Scotsman

(London Kings Cross to Edinburgh)

- The Aberdonian (London

Kings Cross to Aberdeen)

- The

Highlandman (London Kings Cross to Inverness and Fort William)

- The Night Scot (London

Euston to Glasgow)

- The Royal

Highlander (London Euston to Inverness)

- The Night

Riviera (London Paddington to Plymouth and Penzance)

- The Night

Ferry (London Victoria to Paris via Dover / Dunkerque train ferry)

In the interwar years a

large number of generally quite modern overnight sleeping carriages were

inherited by the Big Four railway companies. Yet from the 1920s a great deal of

new sleeper carriages were built by the Big Four. It can only be assumed that

the railways decided to build these new sleeper carriages in order to meet

increased competition from other modes of transport combined with a greater

customer expectation of what should be provided. Sleeping carriages are heavier

passenger for passenger, than ordinary stock and their capacity for revenue

generation is not as high per ton weight as a conventional day carriage. A

typical 12-wheel sleeping car of the interwar period would weigh 40 tons or

more yet only accommodate around 12 berths. Also sleeper carriages could only

be used once a day so would generate less revenue for the railway compared to

day carriages.

However the Big Four

railways were surprisingly lavish in the provisions made for sleeper trains

which at best were likely to be only marginally profitable and at worst a heavy

loss maker. But the reason for this is that they were convinced that passengers

will pay due regard to “on train” facilities and amenities when making the

fundamental decision whether to use the railways in the first place. So for

these reasons the railways continued to build new sleeping carriages. Sleeper

trains were always the type of vehicles which gave the railways publicity and

status, especially on their more celebrated train services and all of the Big

Four made significant steps forward during the interwar period in terms of

sleeper carriage design.

In regard to sleeper train

services there were really only two significant competitors in the Big Four

period and these were the LMS and LNER on the Anglo-Scottish routes. They both

became rather good at sleeping cars and set the trend for the first generation

British Rail sleeping cars in the 1950s.

The traditional British

sleeping car layout (side corridor giving access to a series of compartments with

berths) never varied during the whole Big Four period. Until 1928 when third

class sleeping cars were introduced, there were only first class sleeping cars.

In 1929 the LMS equipped their sleeping cars with a new type of ventilation

system known as the “Thermotank” apparatus. This was a fan driven air

circulation system, driven by a 250 watt electric motor fed from the 24-32 volt

carriage lighting circuit. This served each compartment through a “Punkah”

louvre from a roof level air duct installed below the corridor ceiling. It

could be arranged either to deliver fresh air or extract stale air from the

compartment, and the compartment louvre – which was under passenger control –

could also be swivelled to direct the air over a wide area. Its capacity was 40

cubic feet per minute per berth and the passenger could, if desired, close it

off completely. It proved a remarkably successful idea and became the basis of

the method which was designed into the later LMS and BR standard sleeping cars

right until the Mk III era in the 1980s.

Likewise, the LNER also

started to experiment in 1929 with “forced” ventilation of its sleeping cars.

It called it “Pressure Ventilation” and the system was developed by J. Stone

& Co rather than by Thermotank Ltd as on the LMS.

In one respect, however,

the LNER was more adventurous than the LMS: water heating. Here after

experiments involving keeping pre-heated water warm by using the train lighting

circuits, Sir Nigel Gresley, managed to install what amounted to a totally self-contained

water heating system in sleeping cars by fitting a supplementary belt-driven

generator and storage cells, fully independent of the lighting system. This

added weight but eliminated the need for the use of oil gas water heating. The

LNER was more keen than the LMS in ridding itself of oil gas for heating and

conducted considerable experiments in pursuance of this aim. Meantime, large

gas tanks for heating were always found under LMS carriages.

On the 24th

September 1928 the GWR, LMS and LNER simultaneously introduced proper sleeping

cars for third class passengers. As usual the LMS and LNER on their

Anglo-Scottish routes led the way in terms of concept and quantity and each

offered what amounted to an identical vehicle, an 8-wheeler on a 60ft frame,

the LNER examples being 61ft 6 in over body because of their bow ends. Within

these new carriages, layouts were identical: seven compartments to which access

was gained from end entrance lobbies, each of which also had access to lavatory

and toilet. In both cases compartments were 6ft 4in between partitions, neither

type had outside compartment doors and both of them featured two quarterlights

flanking a central frameless droplight on the compartment side, combined with

large picture windows on the corridor side. Within the compartments, a

convertible arrangement was offered with four berths at night, the upper ones

folding against the partition by day to produce a fairly orthodox side-corridor

third with eight seats per compartment. Pillows and rugs were provided for

night use at a modest supplement.

They were very handsome

vehicles and proved very popular. At the National Railway Museum is preserved a

fully restored LMS example from the very first batch. No.14241 was built by the

LMS at Derby Works and can be seen in the Station Hall.

Photo: LMS third class sleeping car No 14241 built

in 1920s at Derby Works.

Meanwhile the GWR offering

initially was three carriages but these did not display the innovation of the

LMS and LNER carriages. As a result in 1929 it built its own genuine third

class sleeping cars on the LMS / LNER pattern. There were only nine of these

new carriages but they were much more successful. They made full use of the

generous GWR loading gauge and were given bulging sides in order to lengthen

the berths slightly. They also had recessed end entrance doors, and in these

two respects they also set the pattern for the few first class sleeping cars

that the GWR built during the interwar period. Three further third class

sleepers with more restricted dimensions for cross country work were built in

1934.

In 1930 and 1931 the GWR

introduced the only first class sleeping cars built by the company between 1923

and 1947. Again there were only nine built in total and their appearance was

similar to the third class sleeping carriages from 1929.The only other sleeping

cars built to GWR design after its final trio of third class carriages in 1934

were four first class examples to a Hawksworth design in 1951 after

nationalisation. These were 10-berth 12-wheelers like their predecessors but

they were the first and only GWR design sleeping cars to have air conditioning

in any form – and even this was only pressure ventilation of the kind

introduced by the LMS and LNER more than 20 years previously. So this is a sad

reflection on Swindon and their lack of innovation in sleeping car design

compared to the LMS and LNER.

The LMS was the first to

put a properly modern interior into a vehicle whose exterior also indicated an

up-to-date approach to the subject. The instigator was William Stanier.

Interestingly, the first beneficiaries of this approach were the third class

travellers when in 1933 the LMS introduced what were undeniably some of the

most handsomely styled carriages ever to emerge in the modern flush sided look.

They used a new 65 ft underframe and their fixed berths and other internal

amenities echoed existing LNER practice, but for the first time ever in a third

class carriage, an attendant’s compartment was provided. Also by means of

outside air-scoops on the corridor side of the body, fresh air (passed through

oil filters) could enter the carriage and be admitted to compartments by floor

grills in the compartment doors.

The first of these fine

carriages was sent with the Royal Scot locomotive and train on its North

America Tour in 1933, where, largely in consequence of its overall quality

offered to ordinary passengers, it caused something of a sensation by contrast

with American “coach” class travel.

Finally in 1935, the

Stanier approach was applied to first class sleeping cars. The 12-wheel

12-berth style was retained but the body length was increased to 69 ft. The

cars also displayed a slightly bulging profile and this added some 3 ins to the

berth length. By some margin, these were the largest passenger carrying

vehicles ever built by the LMS, but were commendably light in weight. This was

achieved by means of a whole host of new constructional features which Stanier

had incorporated into their design. Most of the change was in the extensive use

of electric arc welding in the bogies, underframe and carriage roof frames. In

terms of their interior décor, the LMS made great use of Rexine and also four

different interior colours were used within each car (three compartments each

in yellow, green, blue and beige) with sanitary ware to match. However the

corridors faithfully maintained LMS traditions; walnut and sycamore. All of the

internal passenger facilities which had evolved after 1923 were also installed.

One of these first class sleeping cars went with the Coronation Scot train on

its North America Tour in 1939.

Soon afterwards the LMS

produced some composite sleeping cars to the new Stanier pattern. These two

were 69 ft vehicles and the only 12-wheel LMS pattern sleeping cars to be built

at Derby. This works had supplied all the LMS third class sleeping cars but

first class sleeping cars tended to be built at Wolverton. In these new

composite sleeping cars, the fixed berth compartments of the 1933 third class

type were combined with the single berths of the 1935 first class cars to

produce a predictable end product. Unlike the earlier composites, they were

arranged with first class at one end and third class at the other end.

By the beginning of the Second

World War both the LMS and LNER were producing high quality sleeping cars.

After the war the LNER moved to flush sided style and only built one further

sleeping car in its own name. This was a mildly experimental Thompson third

class car in 1947 which by means of an interlocking berth layout, enabled both

single and double compartments to be contrived. But in its anticipation of

providing fewer than four berths in a third class compartment, it probably had

some influence on the final designs which were to post-date the onset of BR.

Outwardly, this first Thompson sleeping car bore the most resemblance to the

LMS styling than any of its Gresley forebears. Apart from this one car, the

final LMS and LNER sleeping designs all came into service under BR after nationalisation.

The LMS ordered another

batch of Stanier style first class 12-wheelers (built 1950-51), which were

almost identical to the prewar series, and Thompson on the LNER produced what

amounted to a 10-berth equivalent on an 8-wheel chassis.

It was in the third class

(soon to be second class) where the ultimate fusion of ideas between LMS and

LNER took place. Here, in 1951-51, both Doncaster (LNER) and Derby (LMS) came

up with a new concept for overnight third class travel. Both used a 65ft chassis

and the layout was conventionally side-corridor, but all compartments in both

series were twin berth only and given first class type pressure heating and

ventilation. Their origins may have had something of Thomson’s influence in

them, but a further factor may have been the not uncommon practice during the

Second World War of adding upper berths to some first class compartments. Thus

both LMS and LNER designs played a considerable influence in future BR designs.

Photo: BR (LMS design) first class sleeping car No

M386M built in 1951 at Wolverton. A similar example is now preserved at the

Bluebell Railway.

After nationalisation in

the British Rail era there were two major investments in the sleeper fleet. The

first occurred between 1957 and 1964 when 380 Mark 1 carriages were built to

replace the fleets inherited from the GWR, LMS and LNER.

The Southern Railway didn’t

operate sleeper trains but did provide access to Compagnie International des

Wagon Lits (CIWL) for their Night Ferry service from London to Paris via the

Dover to Dunkerque train ferry. In 1977 operation of the Night Ferry sleeper

train was taken over from CIWL by British Rail (Southern Region) under an

agreement between BR, SNCF and SNCB. SNCF continued to be commercially

responsible for the train as it had been since 1971 and bought the Wagon-Lits

cars from CIWL. In January 1974 SNCF took over publicity of the Night Ferry

sleeper service from CIWL. This ceased on the 31 October 1980 with the final

departure of the Night Ferry sleeper from London, Paris and Brussels.

In 1966 British Rail

launched the InterCity brand for its long distance services. In the same year

the Motorail brand was launched for accompanied cars. These car carrying trains

had their origins in the Anglo-Scottish Car Carrier launched in 1955. These

services offered sleeper accommodation on a train which also carried the

passenger’s own cars. The services grew in popularity and a number of loading

facilities in London expanded to include Kings Cross, Holloway and Marylebone.

There were three kinds of car-carrying trains operated by British Rail. The

CAR-SLEEPER and the CAR-CARRIER service passenger and car travel by the same

train. With the CAR-TOURIST service passenger and car travel by separate

trains, the car travelling through the night and the passenger by day or night.

In the mid 1960s a dedicated station and specialised loading facility was

needed to serve the London area and this was created at Kensington Olympia. On

24 May 1966 the car carrying trains were relaunched as the Motorail

network. This was a great success story for British Rail and in the 1970s with

frustration about long distance car travel and high petrol prices the services

were well patronised for over a decade.

In 1969 the decision was

made to market all of Britain’s sleeper trains as InterCity Sleepers. From its

birth in 1966 the InterCity concept quickly caught the public imagination in

Britain and started a path that would place it among the world leaders in

provision of quality long distance rail transport in the following decades.

Photo: Caledonian Sleeper hauled by class 92

In 1973 British Rail

created Travellers Fare to undertake all its onboard catering. For a while it

was linked with British Transport Hotels, but when these were privatised in the

1980s, Travellers Fare moved to become a division under the control of British Rail.

It provided station facilities and on board catering. In June 1986, Intercity

took over the onboard catering for its services as InterCity Catering Services.

In December 1986 Travellers Fare was privatised.

The second major build of

new sleeping cars under British Rail came about in the early 1980s when 208 air

conditioned Mark III vehicles were built at Derby.

During this

period the list of sleeper trains operated was still very extensive despite

some minor withdrawal of services in the 1960s and 70s including the end of the

Friday night sleeper service from London to Oban. This had been attached to the

19:15 sleeping car train from London Euston to Perth and detached at Stirling.

It returned to London on the 1715 train from Oban to Glasgow and Edinburgh on

Sunday afternoons. In the early 1960s there were also sleeper trains between

London Paddington and Birkenhead, Manchester to Plymouth, and the extension of

the Barrow sleeper to Whitehaven. These had all disappeared by 1975.

By 1975 the BR sleeper

train services included the following:

- London Kings Cross to

Leeds

- London Kings Cross to

Newcastle

- London Kings

Cross to Edinburgh, Fort William and Aberdeen.

- London Euston to

Liverpool

- London Euston to

Manchester

- London Euston to Holyhead

- London Euston to Preston

and Barrow

- London Euston to Carlisle

and Stranraer

- London Euston

to Glasgow and Inverness

- London Paddington to

Milford Haven

- London Paddington

to Exeter, Plymouth and Penzance

- London

Victoria to Paris and Brussels (The Night Ferry)

- Bristol to Glasgow and

Edinburgh

- Nottingham to

Glasgow

In addition to these,

sleepers were provided on a number of Motorail services, many of which were

seasonal. In the late 1970s British Rail talked about a major investment in the

sleeping car fleet including options for 75 ft long air conditioned vehicles

with improved standards of ride, sound insulation, décor and amenities

generally. It was felt that they should be “travelling hotels” with the

provision of a bar / refreshment area in each set of three coaches with

continental breakfast facilities in all compartments. These aspirations were

admirable for the time but were overtaken by major changes in the market for

medium and long distance travel and increasing customer expectations for

overnight accommodations.

In building the new Mark

III sleeper carriages without ensuite facilities, this proved to be a major

mistake by British Rail which continues to hinder the Caledonian Sleeper and

Night Riviera sleeper services today. As a result the market for sleeper

services declined in the 1980s and 90s. Other important factors that affected

the market for sleeper services in this period included the introduction of low

cost domestic flights from a number of regional airports which particularly

affected the Anglo-Irish traffic via the ferry services. This lead to the

closure of the sleeper services from London to Stranraer, Holyhead and

Fishguard. Also significant modernisation and electrification enabled major

journey time reductions on key routes including London to Liverpool,

Manchester, Leeds, Preston, Carlisle, Newcastle and South Wales.

In 1982 InterCity sector of

British Rail was restructured into a series of route units. The Anglo-Scottish sleeper

services were placed in under West Coast and the London to the West Country sleeper

services were under Great Western.

On 11 July 1983 the London

to Penzance sleeper was relaunched as the Night Riviera, designed to complement

the long-established daytime Cornish Riviera.

On 6 May 1987 InterCity

Sleepers was relaunched with Lounge Cars and Sleeper Check In. By this time the

sleeper services were focussed on the Anglo-Scottish services and the

Paddington to Penzance service.

Instead of two competing

Anglo-Scottish services via the WCML and ECML it was combined into a single

service operating out of London Euston with just two 16-car trains each night,

the first to Aberdeen, Inverness and Fort William, and the second to Glasgow

and Edinburgh. Lounge cars were introduced serving simple cooked meals and

light refreshments. Loss of sleeper services from the ECML caused much public

protest as did the loss of the sleeper to Stranraer Harbour.

In 1992 Sleeper and

Motorail services were combined to for InterCity Overnight Services business

unit. By1992 InterCity reached the height of its success and became an

integrated business within British Rail.

On 5 March 1995,

responsibility for operation of the Anglo-Scottish services passed within

British Rail from InterCity West Coast to ScotRail. On 4 June 1996, the service

was relaunched as the Caledonian Sleeper with the Night Caledonian (to

Glasgow), Night Scotsman (to Edinburgh), Night Aberdonian (to Aberdeen), Royal

Highlander (to Inverness) and West Highlander (to Fort William) sub-brands.

But in 1992 the Government

announced plans to privatise the railways in 1994. An early suggestion was to

retain or privatise InterCity as its own train company. InterCity was one of

the best known brands in Britain, with an 82% brand awareness which had taken

25 years to develop. It was a well defined business with a highly successful

track record in profit, performance, marking and quality delivery.

Sadly the Government

decided to split the railways on a route basis and this resulted in the break

up of InterCity as a business and as a brand. Ownership of the InterCity brand

name transferred to the Department of Transport who continue to own it today.

On 31 March 1994 InterCity closes as a corporate business within British Rail

with a final profit of £100 million. On the 28 May 1994 Motorail services were

withdrawn. On the 31 March 1997 British Rail operates its final train which was

the sleeper service from Glasgow to London Euston. It was the end of an era as

British Rail ceased.

Privatisation in the mid

1990s (1993-1997) also presented another major challenge for overnight sleeper

services and resulted in the loss of the Bristol to Glasgow / Edinburgh

service. The Caledonian Sleeper was placed within the Scotrail franchise and

the Night Riviera was part of the Great Western franchise. Yet none of these

offer ensuite facilities in the compartments due to the legacy of Mark III

carriages.

Thus the sleeper

train services evolved into the two routes we see today:

- The Caledonian Sleeper

(London to Glasgow, Edinburgh, Aberdeen, Inverness and Fort

William)

- The Night

Riviera (London Paddington to Penzance)

In 2015 the

Scottish Government decided to separate the Caledonian Sleeper from the

Scotrail franchise and placed it in its own dedicated franchise. This was

awarded to Serco in 2015 and they have placed a £100 million order for 75 brand

new carriages due to be delivered in 2018. These new cars will include business

berths with ensuite toilets and showers and they will be built by CAF.

Meanwhile the Night Riviera sleeper continues to thrive in the Great Western

franchise and this will be extensively refurbished by 2018. So the sleepers are

going from strength to strength.

The

Night Ferry – Britain’s Only International Sleeper:

In 1876, Georges

Nagelmackers, founded the Compagnie International des Wagon Lits (CIWL) in 1876

to operate sleeping car and Pullman services in Europe. He had been inspired by

the Pullman operations of George Mortimer Pullman in America and had the vision

to create an international company operating luxurious trains on well planned routes

across Europe across national frontiers. This was a revolutionary concept for

that time. It was accompanied by a network of hotels at strategically important

places across this network.

In 1894 the Compagnie

Internationale des Grands Hotels was founded as a subsidiary and began

operating a chain of luxury hotels in major cities. Among these were the Hôtel

Terminus in Bordeaux and Marseille, the Hôtel Pera Palace and the Bosphorus

Summer Palace Hotel in Istanbul, the Hôtel de la Plage in Ostend, and the Grand

Hôtel des Wagons-Lits in Beijing

Soon his company had

created a comprehensive network of overnight sleeper services and daytime

Pullman trains across the European Continent. Among these were famous overnight

services such as the Orient Express, the Nord Express, the Sud Express, the

Train Bleu, the Rome Express, etc.

Prior to the First World

War, CIWL held a monopoly being the only group catering to the needs of the

international railroad traveller. Indeed they even expanded to markets outside

Europe with involvement in the Trans-Siberian Railway across Russia. The

Company's trains also reached Manchuria (Trans-Manchurian Express), China

(Peking, Shanghai, and Nanking) and Cairo.

These trains had the

distinctive deep blue livery and golden brass lettering of the CIWL. The

transcontinental services of Wagon-Lits became legendary and synonymous with

comfort, convenience, elegance, allure and above all the safety and privacy of

international overnight rail travel. In the 1930s the Great European Expresses

of Wagon Lits were the accepted ways of European travel. From Calais, sleeper

trains departed every night for Istanbul, Berlin, Rome, Trieste, San Remo,

Monte Carlo, Cannes, Nice and Bucharest. CIWL became the first and most

important modern multinational dedicated to transport, travel agency and

hospitality with activities spreading from Europe to Asia and Africa.

In 1936 CIWL working with

the Southern Railway inaugurated the Night Ferry sleeper service from London to

Paris via the Dover to Dunkirk train ferry. 20 sleeping cars were specially

built by Wagon-Lits so that they could be transferred across the English

Channel on board specially built train ferries. It became Britain’s only

through train service from London to Paris and enjoyed great success. For the

first time the legendary service of CIWL was extended beyond Continental Europe

to Britain. For many years the service was frequented by famous people

including Queen Elizabeth II, the Duke of Windsor, Sir Winston Churchill,

filmstars and government officials.

In 1939 the

Night Ferry service was suspended for the duration of the Second World War,

afterwards it resumed in both directions from 15 Dec 1947. In 1977 operation of

the Night Ferry sleeper train was taken over from CIWL by British Rail

(Southern Region) under an agreement between BR, SNCF and SNCB. SNCF continued

to be commercially responsible for the train as it had been since 1971 and

bought the Wagon-Lits cars from CIWL. In January 1974 SNCF took over publicity

of the Night Ferry sleeper service from CIWL. This ceased on the 31 October

1980 with the final departure of the Night Ferry sleeper from London, Paris and

Brussels.

Nightstar

– Britain’s stillborn International Sleepers via the Channel Tunnel:

In the 1970s

when British Rail was giving initial considerations to the Channel Tunnel

project a number of initial ideas regarding possible sleeper routes were

mentioned. These possible international sleeper routes could have included:

- London to Lille, Brussels

and Amsterdam

- London to Lille,

Brussels, Cologne and Hamburg

- London to

Lille, Brussels, Cologne and Frankfurt

- London to Lille,

Strasbourg, Munich and Salzburg

- London to Lille,

Strasbourg, Munich and Innsbruck

- London to Lille, Strasbourg

and Chur

- London to

Lille, Strasbourg and Interlaken

- London to Paris, Lausanne

and Milan

- London to Paris, Lyons,

Marseilles and Nice

- London to Paris,

Toulouse, Port Bou, Barcelona and Madrid

- London to

Paris, Bordeaux, Irun and Madrid / Lisbon

Later in the late 1980s and

early 1990s as the Channel Tunnel project became more established further

consideration of international sleeper services was explored. The Nightstar sleeper trains were proposed

overnight sleeper services from various parts of United Kingdom to continental

Europe, via the Channel Tunnel. To run alongside the Eurostar and north of London day-time Regional Eurostar services, the Nightstar was the last part in a

round-the-clock passenger train utilisation of the Channel Tunnel.

Unfortunately due to concerns about viability, the Nightstar sleeper proposal

was discontinued in 1997 despite carriages having been built for it. Some of

the cars built for the service were sold to VIA Rail in Canada.

The cars were

air-conditioned with power operated doors and designed to meet the safety

standards of each country they would run through, the most stringent of these

requirements being for the Channel Tunnel. A fleet of 139 cars were originally

ordered, broken down as 47 seated cars, 72 sleeper cars and 20 service

vehicles. The cars would have normally been configured as 9 seven-car and 9

eight-car sub-sets, with four spares (two seated cars and two service

vehicles). The trains would have run as either individual sub-sets (for beyond

London services and to some European destinations), or as two sets coupled

together (from London and through the Tunnel). As the trains were designed to

run as fixed formation sub-sets, only the two outer ends of each sub-set had

buffers and draw gear.

Photos - top and below: The carriages of the ill-fated Nightstar

Sleepers via Channel Tunnel

Seven-car sub-sets, for

services beyond London:

- Three seated cars

- Service vehicle

- Three sleeper

cars

Eight-car sub-sets, for

London services:

- Two seated cars

- Service vehicle

- Five sleeper

cars

Each seated car

had 50 reclining seats in a 2+1 configuration across the aisle, with room for

luggage underneath. Each sleeper car had 20 beds, split over 10 cabins (two per

cabin). All cabins had an en-suite toilet and basinette, while six cabins had

an en-suite shower. The beds could be folded into the wall to provide seating.

The service vehicle had bench style seating for 15 passengers in a lounge area,

a catering area, large luggage area and staff accommodation in the centre, and

a large cabin with two beds, designed to be accessible to wheel chair users, at

the other end. The seated area would have been coupled to the seated cars and

the cabin end to the sleeper cars. When the service was first proposed in 1992

route options were:

- London to Brussels and

Amsterdam / Cologne (splits at Aachen)

- London to

Brussels and Dortmund / Frankfurt (splits at Aachen)

- Plymouth to Brussels

- Swansea and Cardiff to

Brussels

- Glasgow to

Brussels

The Plymouth and Swansea

trains would each have been formed of a single seven-car sub-set, and the

Glasgow train of two seven-car sub-sets. The Plymouth and Swansea trains would

be diesel hauled beyond London by a class 37/6 and Generator set, with the

Glasgow train electric hauled. At London Kensington Olympia, the Glasgow train

would be split and the two sub-sets attached to the respective Swansea and

Plymouth trains to form one train to Paris and one to Brussels. They would be

electric hauled from London to the continent.

Eventually the final route

options included trains on five routes to Glasgow, London, Manchester

Piccadilly, Plymouth and Swansea in the UK to and from Amsterdam, Dortmund and

Frankfurt. Sadly these aspirations were not to be and the Nightstar project was

stopped in 1997 along with the Regional Eurostar proposals. So only the

Eurostar aspect was realised from the original concept of the Channel Tunnel

trains.

The carriages intended for

the Nightstar project were sold to VIA Rail in Canada.

Future

Opportunities for International Sleepers from London:

Despite the end of the

Night Ferry service in 1980 and the failure of the Nightstar concept in the

1990s in the future there may be opportunities to re-examine the potential for

international sleepers from London via the Channel Tunnel subject to the

outcome of BREXIT and the regulations that govern the Channel Tunnel.

But if such opportunities

are to be realised route destinations, timings, pricing and onboard amenities

for such services have to be carefully considered. Also it is absolutely vital

that such services are heavily promoted and marketed.

It should focus on major

holiday destinations (French Riviera and the Alps) and city destinations to

maximise the potential to capture business and leisure travellers.

Destinations

from London that could be explored may include:

- The French Riviera

(Marseilles, Cannes, Monte Carlo and Nice)

- The Ski Resorts of the

Alps

- Barcelona and Madrid

- Madrid and Lisbon

- Milan and Rome

- Hamburg and Berlin

- Copenhagen,

Oslo and Stockholm

So with the

right product, routes and adequate marketing there may be potential to make

such overnight sleeper services from London to Continental Europe a success.

BRITAIN’S

SLEEPERS TODAY:

The

Night Riviera (London Paddington to Penzance):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RypBSOouz3s (promotional

film for refurbished Night Riviera sleeper service by Great Western Railway

from 2018)

Photo: The Night Riviera sleeper at London

Paddington

The Night Riviera sleeper

is operated by Great Western Railway and usually comprises four or five sleeper

coaches (but up to six at peak times), a restaurant car and two day coaches. It

usually is ready waiting in Platform 1 at London Paddington by 2100 with

passengers able to board at around 2230. Sleeper passengers are able to access

the First Class Lounge at Paddington while waiting for the train. Today the

Night Riviera sleeper is very popular and is often fully booked especially in

summer.

The service on the Night

Riviera differs from the Caledonian Sleeper. Its much later departure time

allows passengers to get an evening meal in London so there is less focus on

serving food (although with the brasserie lounge car on the refurbished trains

this is set to change). It is more of a drinks and light refreshments service

with all berth passengers offered a drink and a light breakfast in the morning

rather than an optional paid for breakfast. The refurbished train in 2018 is

set to transform its appeal. Indeed with the service often fully booked, it is

thought that there could be enough demand to justify a second service

especially in peak summer months.

The Night

Riviera is the only way of reaching London from Cornwall before 0900, doing a

full day’s business and then returning home in comfort. For a region where

incomes are far below the national average and house prices are high, this

ability for businesses to punch above their weight in London is vital.

Therefore the Night Riviera’s role in creating and sustaining jobs in Cornwall

is out of all proportion to the number of passengers it carries. Indeed it

makes a profit and is going from strength to strength. Even though the distance

covered is small compared with some sleeper services in Continental Europe,

daytime journey times between London and Cornwall remain long. So the Night

Riviera is a genuine lifeline service.

The

Caledonian Sleeper (London to Scotland):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gJm5glAiU58 (Launch of the

new dedicated Caledonian Sleeper franchise operated by Serco in March 2015)

Photo: The Caledonian Sleeper at Fort William

The Caledonian Sleeper is

operated as a dedicated franchise by Serco and it is very popular due to the

vast distances from the Scottish Highlands to London. The Edinburgh and Glasgow

portions are very busy despite the good rail and air links from these cities to

London. The Highlands portion are also very busy especially in the peak summer

season when they can get fully booked.

Since creation of the

dedicated franchise in April 2015 by the Scottish Government and its awarding

to Serco the Caledonian Sleeper is enjoying a great revival. Massive investment

is going into its promotion and new rolling stock. A concerted effort has also

been made to maximise its Scottish credentials, improving catering provision

and allowing bookings 12 months in advance. The new trains coming into service

in 2018 will offer a wider range of accommodations and potentially increase

capacity. They also will be a world away from today’s BR era Mark III

carriages. However caution will be required to ensure that the new service

meets modern day expectations but yet remains cost effective and affordable to

its market.

The train is operated in

two services both of which are 16 carriages long. The first is the Lowland

Sleeper serving Glasgow and Edinburgh. The second is the Highland Sleeper

serving Edinburgh and then splitting into three sections to serve Aberdeen,

Inverness and Fort William. It is the longest scheduled domestic passenger

train in Britain and currently uses London Euston.

The Caledonian Sleeper is

also vitally important for the Scottish Highlands and enables businesses to

punch above their weight in London. So its role in creating and sustaining jobs

in the Scottish Highlands is out of all proportion to the number of passengers

carried by the Caledonian Sleeper. Even though the distance covered is small

compared with some sleeper services in Continental Europe, daytime journey

times between London and Scotland remain long particularly to the Scottish

Highlands. So the Caledonian Sleeper is a genuine lifeline service.

The service is going from

strength to strength due to a combination of growing dissatisfaction with the

airlines and increased awareness of the train due to increased investment and

promotion. Having its own dedicated franchise was a great help in raising the

awareness of the Caledonian Sleeper. The investment in new trains will also

significantly upgrade the onboard service offer. Also increasingly people want to

make sleeper trains part of their holiday experience so it is increasingly

important to work with tourism bodies to promote the region served. The sleeper

train can, if given the right investment and promotion, become an icon and

symbol of the region served and indeed a holiday experience in their own right.

Indeed Lonely Planet's 2016

Best in Travel guide rates Serco's London-Fort William Caledonian Sleeper

service the world's best sleeper route.

Serco’s plans are well

underway to transform the iconic Caledonian Sleeper service into an outstanding

hospitality service that is emblematic of the best of Scotland. Work to build

75-new coaches for the Caledonian Sleeper will soon get underway after Serco

agreed signed key contracts to manufacture 75 new Sleeper coaches. Serco signed

contracts with Construcciones y Auxiliar de Ferrocarriles (CAF) for the

manufacturing of the new fleet and Alstom UK for maintenance of the coaches.

The new coaches to be

delivered in 2018 will offer four innovative ways to travel in comfort on the

Sleeper service; Cradle Seats, Pod Flatbeds, Berths and En-Suite Berths, and

will include a Brasserie style Club Car for dining. Edinburgh-based designer

Ian Smith is responsible for creating a ‘contemporary’ style for the new

coaches. The Cradle Seats will provide an improved seated experience with

reclining seats and footrests. The Pod Flatbeds will fully recline from a seat

into a bed and offer a privacy screen and a reading light. The Berths ensure

privacy and personal security as well as all the facilities the modern

traveller needs. The En-Suite Berths are also available and provide en-suite

toilet and shower facilities.

The new Caledonian Sleeper

service with its new CAF sleeper cars from 2018 will provide a great

alternative to other rail and air travel between London and Scotland. After a

relaxing night on board the service, sleeping while on the move, guests will

arrive at their destination first thing in the morning refreshed and ready to

go.

Other plans to transform

the Caledonian Sleeper service into an outstanding hospitality offering that is

emblematic of the best of Scotland are well underway. This includes all aspects

of the operation of the Caledonian Sleeper franchise; marketing, sales,

hospitality service on the trains, vehicle maintenance and the provision of

facilities at stations for guests. So it is enjoying a great revival.

In the future there may be

scope to expand capacity on the Fort William and Inverness portions of the

Caledonian Sleeper during the summer season. Then as demand increases there may

be a case for additional rolling stock. Additionally there may be options to

explore to serve more destinations in Scotland such as Oban, Wick or Thurso for

example. As the core route from London to Scotland becomes full then there may

be scope to grow the service and add an additional route to the Midlands and

South West, after all the airlines do well on these routes so clearly there is

a potential market there to explore for the Caledonian Sleeper.

Lastly with the

construction of HS2 due to bring disruption to London Euston, the Caledonian

Sleeper is actively considering relocating the service to London Kings Cross.

This station will also be more fitting environment for this iconic service.

However the platforms cannot accommodate 16 car trains so the service may have

to be split into three portions in future instead (two 12-car trains and one 8

car train).

LESSONS

FOR THE FUTURE:

As I have said

in this article Britain’s sleeper services are going from strength to strength

due to a combination of growing dissatisfaction with the airlines and increased

awareness of the trains due to increased investment and promotion. Also

increasingly people want to make sleeper trains part of their holiday

experience so it is increasingly important to work with tourism bodies to

promote the region served. The sleeper train can, if given the right investment

and promotion, become an icon and symbol of the region served and indeed a

holiday experience in their own right.

So there are

some key factors for success including:

- Targeted and focused routes with convenient timings and

ticketing offer that perform a

lifeline role for their regions to link them

with major cities or capitals.

- Investment to keep pace with customer expectations and remain

competitive including

high quality vehicles, hospitality and

onboard offer

- Marketing and promotion of the service to make it a symbol of the

regions served and a

holiday experience in its own right.

Perhaps this success in

Britain can be an inspiration to reinvigorate overnight sleeper services

elsewhere across Europe where they are neglected and declining.

LINKS:

The Caledonian Sleeper

The Night Riviera

Nice article with good Insights. thank you for sharing.

ReplyDelete