Austrian and Hungarian immigrants contributed immense to the US culture and economy.

America, after its re-discovering by Christopher Columbus in 1492, was the first place of Austrian and Hungarian to immigrate to. It was the land of hope and possibilities, and the young USA, as the former colony, needed immigrants ... and these immigrants found vast opportunities in a country that was more or less "empitied" of humans, after the first contact with Europeans, and their, unknown to the indigen population and themselves, biological weapons - diseases for that the American natives had nothing to fight against, as they had been unknown to them, after eons of "isolation".

by Earl of Cruise

Emmigrants in the BALLIN STADT, a center for emmigrants initiated by Albert Ballin, after Cholera epidemiic in Hamburg 1892 - Source: BALLIN STADT

Although some estimates suggest that the numbers of Austrians in the

United States have represented less than one tenth of 1 percent of the

entire U.S. population, Austrian immigrants and Austrian Americans have

had a profound impact on the arts, sciences, and popular culture of the

United States.

Austrian immigration provides an example of the difficulty of defining certain American immigrant populations because of changing borders and ethnic identifications. An analogue of modern Austria existed in ancient times as a province of the ancient Roman Empire. In later centuries, the region persisted, at various times and in various forms and sizes, as a duchy, as a powerful empire in its own right, and as a partner with Hungary in the Austro- Hungarian Empire.

Austrian immigration provides an example of the difficulty of defining certain American immigrant populations because of changing borders and ethnic identifications. An analogue of modern Austria existed in ancient times as a province of the ancient Roman Empire. In later centuries, the region persisted, at various times and in various forms and sizes, as a duchy, as a powerful empire in its own right, and as a partner with Hungary in the Austro- Hungarian Empire.

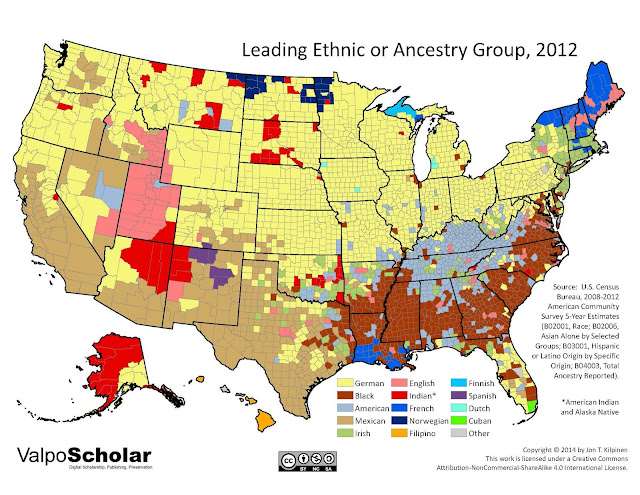

Leading Ethnic or Ancestry Group in 2012 - Source: US Census, © Jon T. Kilpinen

The

modern state of Austria was not established until 1919, as a consequence to the Verailles Treaty. Therefore,

pre-1919 statistics on Austrian immigration cannot be authoritative for

several reasons. For example, under the Austrian and Austro-Hungarian

empires, members of many ethnic groups were technically Austro-Hungarian

citizens. These included Serbs, Czechs, and Slovenians. However, when

these peoples, who were technically Austro-Hungarian nationals, immigrated to

the United States, American immigration officials did not always

distinguish between ethnicity and national citizenship. For this reason, Austro-Hungarian immigrants of Serbian descent might have been recorded as

“Serbians,” not as “Austro-Hungarian”, as there was a Serbian kingdom existing in those days. Conversely, immigration officials were

also not always clear about distinctions between Austria and its fellow

German-speaking neighbor Germany. And all to often they changed the original spelling to their known and used English spelling ... It is likely that more than a few

immigrants who should have been recorded as Austrians were listed as

Germans.

Profile of Austro-Hungarian immigrants

*Immigrants who obtained legal permanent resident status in the United States - Source: Department of Homeland Security, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, 2008

Four

different periods in U.S and European history have seen the most

significant numbers of immigrants from Austria and Hungary. The first occurred

before the American Revolution and was prompted by quests for religious

freedom. Much of German speaking Europe from the medieval times through the 17th and the 19th centuries consisted of dozens of small duchies,

principalities, free cities, monasteries, clergical states and kingdoms, resulting from the federal organisation of the Holy Roman Empire - of German Nation. The religious preferences of their

rulers - who could be either Roman Catholics or Protestants - were usually

identified as the state religions this religious rule was caused by a compensation treaty in Agusburg mid 16th. century to prevent a religious war back then. Citizens of other religious

persuasions were often discriminated against, if not persecuted

outright. This religious intolerance and the strict medieval guild structures for handcrafters and other professions, often led to emigration. E.g. the son had to became a professional in the same profession his father and grandfather had.

The

first Austro-Hungarian immigrants on American shores, protestants, who arrived in 1734 in

what is now the state of Georgia, came from the Salzburg area, where

Roman Catholicism was dominant. Several hundred in number, of ~50 families, they established a community called Ebenezer not far from Savannah. After the

American Revolution (1775-1783), one of them, Johann Adam Treutlen, became the first governor of the new state of Georgia. When

U.S. president Bill Clinton later proclaimed September 26, 1997, to be

Austrian American Day, he recalled the contributions of Georgia’s early

Salzburger pioneers.

The

second major wave of immigrants began in 1848, when a series of prodemocracy rebellions broke out in all Europe, including Austria-Hungary, and what would become modern, late 19th century, early 20th century, Austro-Hungary.

1848 a first democratic parliament was established in Frankfurt, that elaborated a federal, democratic constition. The head of state, then a German federal nation, should have been the king of Prussia - but he refused, as he was unsure what the other German kings and dutches may think of him, accepting that constitution. The following suppression of these revolutions led to a massive immigration to the

United States of many of the intellectuals who had waged them. Called

the “Forty-eighters”, these Austrians tended now to settle in large American

cities in the North and Midwest, where a number of them became active

in the abolitionist movement. As the most with that background - e.g. the German Carl Schurz.

Immigration from Austro-Hungary from 1860 to 2008 - Source:

Department of Homeland Security, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics,

2008. Figures include only immigrants who obtained legal permanent

resident status

The

third immigration wave was the largest and took place during the first

decade of the 20th century, during which more than two million Austro-Hungarian arrived on American shores, in large part because of the economical,

political and ethnic conflicts mainly on the Balkan that eventually led to the outbreak of

World War I after the murdering of Erzherzog Franz Ferdinand, the presumtive heir to the throne of Austro-Hungary, and his wifeby Gavrilo Princip.

The fourth and final wave was motivated by the autocratic government in austria, later Nazi oppression after the "re-connection of Austria, and after World War II.

This wave finally can be called a real Austrian immigration wave, as now it was from the present state of Austria. During the years leading up to WWII, many Austrian Jews fled

their homeland to escape the Holocaust. Also democrats, artists, etc. that did not see any longer a chance living a free life, as prior to the Nazi German occupation, Asutria was an autocratic governed country. After the war ended in 1945,

more Austrians - this time from many backgrounds - immigrated to escape the

desolation and disorganization left in the wake of WWII. From the mid-1930’s

through the mid-1950’s, approximately 70,000 Austrians arrived in the

United States. After Austria emerged as a prosperous, democratic country

during the 1960’s, Austrian immigration to the United States became

negligible.

Austrian

immigrants have proven that even a small immigrant population can

strongly affect the cultural and intellectual life of America, as

Austrian immigrants and Austrian Americans have been prominent in a wide

array of fields. From the earliest days of motion pictures, Austrian

immigrants and their offspring have been prominent in cinema. Examples

include silent-screen star Ricardo Cortez, born Jacob Krantz, the celebrated dancer Fred Astaire, born Frederick Austerlitz, both families of Austrian descend, actor Peter Lorre, born László Löwenstein, in Rosenberg and legendary screen star Hedy Lamarr.

Hedy Lamarr traveled as Hedwig Eva Maria Mandel, born Kiesler, onboard NORMANDIE to the States, escaping her control-freak husband who mingled with the Nazis.

You may say, that she boarded as Hedwig Eva Maria Mandel and descended in New York as Hedy Lamarr from NORMANDIE.

At the beginning of World War II, Lamarr and composer George Antheil developed a radio guidance system for Allied torpedoes, which used spread spectrum and frequency hopping technology to defeat the threat of jamming by the Axis powers. Although the US Navy did not adopt the technology until the 1960s, the principles of their work are now incorporated into modern Wi-Fi, CDMA, and Bluetooth technology, and this work led to their induction into the National Inventors Hall of Fame in 2014.

|

During the late twentieth/early twenty-first centuries, three of the

best-known actors in America were of Austrian descent: Arnold Schwarzenegger, who was a superstar during the 1980’s and 1990’s and

became governor of California in 2003; Erika Slezak, with a real European descent - of Czech, Austrian and Dutch, of One Life to Live, and Natalie Portman, who played

Princess Amidala in the enormously popular StarWars films.

Three of

Hollywood’s most respected directors of the early and mid-twentieth

century were of Austrian descent - Fritz Lang, Otto Preminger, and Billy Wilder. One of the most popular musicals in Broadway and Hollywood film

history, "The Sound of Music", is based on the true story of an Austrian

family that eventually immigrated to America.

Already

well known before she arrived in the United States during the 1930’s,

Hedy Lamarr (right) became one of Hollywood’s most glamorous leading

ladies. In 1953, she naturalized as an American citizen. This film still

is from Comrade X (1940), in which she plays opposite Clark Gable

(center) as a Russian streetcar conductor anxious to spread the

communist message - Source: Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images

Other

areas of endeavor in which Austrians in America have triumphed have

included law, Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, musical

composing Arnold Schoenberg and Erich Korngold, physics Wolfgang Pauli, literature Franz Werfel, and food preparation Wolfgang Puck.

A little-known area in which America has been greatly influenced by

Austrian immigrants is that of skiing, as much of the art and practice

of alpine skiing in the United States follows Austrian traditions first

taught in American ski resorts by such immigrants as Hannes Schneider

and Stefan Kruckenhauser.

Although most Hungarians who emigrated to the United States arrived

between 1890 and the start of World War I in 1914, the most significant

Hungarian immigration took place during the 1930’s. The spread of

fascism and Nazism in Europe forced thousands of highly educated

scientists, scholars, artists, and musicians to leave Hungary under the Miklós Horthy regime and

Central Europe to find safe haven in America.

Although

Hungarian presence in North America reaches back to 1583, when Stephen Parmenius of Buda reached American shores, the first significant

Hungarian political immigration took place in the early 1850’s.

Following the defeat of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848-1849, several

thousand Hungarians found haven in the United States. Most of them came

with the intention of returning to Europe to resume their struggle

against the Austrian Empire, but a new war of liberation never

materialized. However, many émigrés repatriated to Hungary after the

Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, which transformed the Austrian

Empire into the dualistic state of Austria-Hungary. Before their

repatriation, however, close to one thousand Hungarians - 25 percent of

all Hungarians then in the United States - had served in the Union Army

during the Civil War. Almost one hundred of them served as officers;

among them were two major generals and five brigadier generals. Many

other Hungarians never repatriated and instead joined the ranks of

American professionals, businessmen, and diplomats. They were able to do

so because over 90 percent of them came from the ranks of the upper

nobility and the gentry, and were thus learned enough, with sufficient

social and linguistic skills, to impress contemporary Americans.

They were drawn to America by the work opportunities that did not exist at home. Even though Hungary itself was then being urbanized and industrialized, its development was not sufficient to employ all the peasants who were being displaced from the countryside. In the course of time, about 75 percent of these “guest workers” - two-thirds of whom were young men of marriageable age - transformed themselves into permanent immigrants. They established families in the United States and became the founders of Hungarian churches, fraternal associations, and scores of local, regional, and national newspapers geared to their educational levels.

The next wave of immigrants, known as the “Great Intellectual Immigration,” appeared during the 1930’s, in consequence of Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in Germany in 1933 and the resulting rapid increase of anti-Semitism and antiliberalism in central and Eastern Europe. Although only about fifteen thousand Hungarians immigrated during the 1930’s, this period brought thousands of highly educated scientists, writers, artists, composers, and other professionals to the United States. Ethnic Magyars constituted only a small segment of this Intellectual Immigration, but their impact was so great and widespread that many people began to wonder about the “mystery” of Hungarian intellectual talent. The impact of this immigration on the United States was felt through the rest of the twentieth century. Several Hungarian scientists played a major role in the development of the atomic bomb during World War II. Others, such as John von Neumann, were later in the forefront of the birth of the computer, and several became Nobel laureates.

The post-World War II period saw the coming of several smaller immigrant waves that may have brought as many as another 130,000 Hungarians to the United States. These immigrants included about 27,000 displaced persons who represented the cream of Hungary’s upper-middle-class society. Most of them left Hungary after the war for fear of the Soviet domination of their homeland. Postwar immigrants also included about 40,000 so-called Fifty-Sixers, or “Freedom Fighters”, who left Hungary after the suppression of the anti-Soviet and anticommunist Hungarian Revolution of 1956.

The next three decades saw a trickle of continuous immigration of about 60,000 immigrants who escaped from Eastern Europe. The collapse of communism and Soviet rule in 1989-1990 altered the situation. With the freedom to emigrate restored, and the attractive opportunities in the United States, many highly trained Hungarians came in quest of greater economic opportunities. One German scholar called these postcommunist immigrants “Prosperity Immigrants” - people who during the Soviet era had lost much of the idealism and ethical values of their predecessors. What most of them wanted was primarily economic success. While searching for affluence in the United States, they contributed their know-how to American society, which valued and rewarded them accordingly.

By the early twenty-first century, the immigrant churches, fraternals, newspapers, and other institutions of immigrant life were in the process of disappearing. Few of the new Hungarian immigrants have shown an inclination to support the traditional institutions that were important to their predecessors. Given this reality, and the unlikelihood that there would be another major immigration from Hungary, it seemed only a question of a few years before all of these institutions would vanish. According to the 2000 U.S. Census, 1.4 million Americans claimed full or primary Hungarian descent. Of these, 118,000 (8.4 percent) still used Hungarian as a language of communication within their families. By contrast, 1.8 million claimed Hungarian ancestry in 1980, and 180,000 were still speaking Hungarian at home).

USA as we see it today would never have become what it is, without the immigrants that came to the once country of hope and chances.

| Country of origin | Hungary |

| Primary language | Hungarian |

| Primary regions of U.S. settlement | East Coast |

| Earliest significant arrivals | Early 1850’s |

| Peak immigration period | 1880’s-1914 |

| Twenty-first century legal residents* | 10,494 (1,312 per year) |

Profile of Hungarian immigrants

*Immigrants who obtained legal permanent resident status in the United States.

Source: Department of Homeland Security, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics, 2008

The next

significant wave of Hungarian immigrants were the turn-of-the-century

“economic immigrants.” These were mostly peasants and unskilled workers

who came in huge numbers, primarily as guest workers, to work in steel

mills, coal mines, and factories. A great number of these emmigrants had been transported by AUSTRO AMERICANA across the Atlantic, besides their rivals in immigrant tade. Of the nearly two million immigrants

from Hungary during the four decades leading up to World War I, about

650,000 were true Hungarians, or Magyars. The remaining two-thirds were

Ruysins, Slovaks, Romanians, Croats, Serbs, and Hungarian German. Of

the 650,000 ethnic Magyars, close to 90 percent were peasants or

unskilled workers who had recently emerged from the ranks of the

peasantry.They were drawn to America by the work opportunities that did not exist at home. Even though Hungary itself was then being urbanized and industrialized, its development was not sufficient to employ all the peasants who were being displaced from the countryside. In the course of time, about 75 percent of these “guest workers” - two-thirds of whom were young men of marriageable age - transformed themselves into permanent immigrants. They established families in the United States and became the founders of Hungarian churches, fraternal associations, and scores of local, regional, and national newspapers geared to their educational levels.

Immigration from Hungary 1850 - 2008 - Source:

Department of Homeland Security, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics,

2008. Figures include only immigrants who obtained legal permanent

resident status. There are no data for specifically Hungarian

immigration before 1860

The mass

European immigration that occurred during the four decades before the

outbreak of World War I came to an end in 1914. Although it resumed at a

slower pace after the war, the federal immigration quota laws of 1921,

1924, and 1927 put an end to this immigration, especially for those from

southern and eastern Europe. This decline of immigration was furthered

by the collapse of the stock market in 1929 and the resulting Great

Depression. Consequently, fewer than thirty thousand Hungarians

immigrated to the United States during the 1920’s.The next wave of immigrants, known as the “Great Intellectual Immigration,” appeared during the 1930’s, in consequence of Adolf Hitler’s rise to power in Germany in 1933 and the resulting rapid increase of anti-Semitism and antiliberalism in central and Eastern Europe. Although only about fifteen thousand Hungarians immigrated during the 1930’s, this period brought thousands of highly educated scientists, writers, artists, composers, and other professionals to the United States. Ethnic Magyars constituted only a small segment of this Intellectual Immigration, but their impact was so great and widespread that many people began to wonder about the “mystery” of Hungarian intellectual talent. The impact of this immigration on the United States was felt through the rest of the twentieth century. Several Hungarian scientists played a major role in the development of the atomic bomb during World War II. Others, such as John von Neumann, were later in the forefront of the birth of the computer, and several became Nobel laureates.

The post-World War II period saw the coming of several smaller immigrant waves that may have brought as many as another 130,000 Hungarians to the United States. These immigrants included about 27,000 displaced persons who represented the cream of Hungary’s upper-middle-class society. Most of them left Hungary after the war for fear of the Soviet domination of their homeland. Postwar immigrants also included about 40,000 so-called Fifty-Sixers, or “Freedom Fighters”, who left Hungary after the suppression of the anti-Soviet and anticommunist Hungarian Revolution of 1956.

The next three decades saw a trickle of continuous immigration of about 60,000 immigrants who escaped from Eastern Europe. The collapse of communism and Soviet rule in 1989-1990 altered the situation. With the freedom to emigrate restored, and the attractive opportunities in the United States, many highly trained Hungarians came in quest of greater economic opportunities. One German scholar called these postcommunist immigrants “Prosperity Immigrants” - people who during the Soviet era had lost much of the idealism and ethical values of their predecessors. What most of them wanted was primarily economic success. While searching for affluence in the United States, they contributed their know-how to American society, which valued and rewarded them accordingly.

By the early twenty-first century, the immigrant churches, fraternals, newspapers, and other institutions of immigrant life were in the process of disappearing. Few of the new Hungarian immigrants have shown an inclination to support the traditional institutions that were important to their predecessors. Given this reality, and the unlikelihood that there would be another major immigration from Hungary, it seemed only a question of a few years before all of these institutions would vanish. According to the 2000 U.S. Census, 1.4 million Americans claimed full or primary Hungarian descent. Of these, 118,000 (8.4 percent) still used Hungarian as a language of communication within their families. By contrast, 1.8 million claimed Hungarian ancestry in 1980, and 180,000 were still speaking Hungarian at home).

USA as we see it today would never have become what it is, without the immigrants that came to the once country of hope and chances.

Further Reading for Austrian immigrants

- Boernstein, Henry. Memoirs of a Nobody. Edited and translated by Steven Rowan. Detroit: Wayne University Press, 1997. Autobiography of a Forty-eighter that provides insights into a littleknown source of American activism during the nineteenth century.

- Leamer, Laurence. Fantastic: The Life of Arnold Schwarzenegger. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2006. Perhaps the definitive biography of the most famous Austrian American of all time, the bodybuilder and film star who became governor of California in 2003.

- Naiditch, Hannah. Memoirs of a Hitler Refugee. New York: Xlibris, 2008. Similar to Perloff’s book but broader in scope.

- Perloff, Marjorie. The Vienna Paradox. New York: New Directions, 2004. Autobiography of a major American literary critic who was Jewish and fled Vienna as the Holocaust approached. Records the impact of specifically Viennese culture on Austrian and American thought.

- Spalek, John, Adrienne Ash, and Sandra Hawrylchak. Guide to Archival Materials of German-Speaking Emigrants to the U.S. After 1933. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1978. Invaluable for historical or genealogical research into German/Austrian immigration during the mid-twentieth century, especially Holocaustrelated immigration.

- Fermi, Laura. Illustrious Immigrants: The Intellectual Migration from Europe, 1930-1941. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969. The wife of Nobel laureate Enrico Fermi, who built the first experimental nuclear reactor, Laura Fermi provides an intimate internal view of those whom she calls Europe’s “illustrious immigrants,” who include such prominent Hungarians as Leo Szilárd, Eugene Wigner, and Edward Teller.

- Lengyel, Emil. Americans from Hungary. 1948. Reprint. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1974. Written by a prominent Hungarian American journalist, this volume is the earliest Englishlanguage synthesis of Hungarian American history and draws heavily on earlier Hungarianlanguage publications.

- Puskás, Julianna. Ties That Bind, Ties That Divide: One Hundred Years of Hungarian Experience in the United States. Translated by Zora Ludwig. New York: Holmes&Meier, 2000. Scholarly, statisticsfilled synthesis of Hungarian American history by a native Hungarian scholar who devoted much of her life to researching “economic” emigrants to the United States of the early twentieth century. Volume says little about post-World War II political immigrants.

- Széplaki, Joseph. Hungarians in America, 1583- 1974: A Chronology and Fact Book. Dobbs Ferry, N.Y.: Oceana, 1975. Short but useful summary of Hungarian American history by a librarian who was not a professional historian.

- Várdy, Steven Béla. Historical Dictionary of Hungary. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press, 1997. First comprehensive encyclopedic work on Hungarian history in English.

- _______. The Hungarian Americans. Rev. ed. Safety Harbor, Fla.: Simon Publications, 2001. The first English-language synthesis of Hungarian American history by a trained Hungarian American historian.

- _______. The Hungarian Americans: The Hungarian Experience in North America. New York: Chelsea House, 1989. Short, heavily illustrated work. Based to a large degree on the first edition of the work but also includes the Canadian Hungarian Americans. Contains an introductory essay by Daniel Patrick Moynihan.

- _______. Magyarok az òjvilágban. Budapest: Magyar Nyelv és Kultúra Nemzetkšzi Társasága, 2000. This 840-page book on Hungarians in the New World, published by the International Association of Hungarian Language and Culture, is the largest synthesis of Hungarian American history yet published. Although still not available in English, this Hungarian edition contains a thirtyfive- page English summary.

Comments

Post a Comment